Reading Plutarch didn’t just teach me history. It cut.

(Side note: I can’t stress enough how reading Plutarch was fundamental to forging myself)

Some stories don’t fade, they echo, they etch themselves into you. This was one of them.

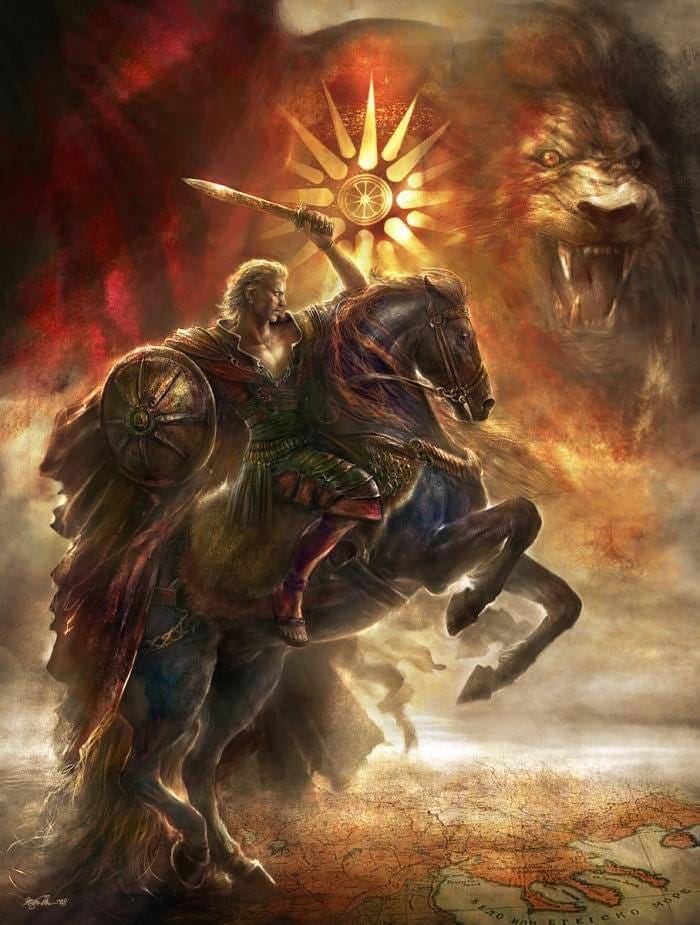

On his first campaign, Alexander didn’t conquer, he obliterated.

He wanted the praise of his father, King Philip.

Not as a prince playing soldier, but as a man worthy of the throne.

So he drowned his enemies in blood, left nothing standing.

Philip was horrified.

Disgusted, not by the failure, but by the success.

By the ruthlessness of it.

Alexander never forgot the shame. It forged something in him.

From that day, he vowed: conquest without cruelty. Expansion without erasure.

Not out of softness.

Out of vision.

He didn’t just want land, he wanted fusion.

He ordered his generals to intermarry with the people they conquered.

He forced the adoption of local customs, not to destroy, but to blend.

He believed a civilization should spread its light without dimming others.

This wasn’t empire.

It was alchemy. A unification of East and West under the banner of logos, reason, virtue, philosophy.

He saw culture as something to uplift, not erase. Assuming they deserved it by how they treat their own

Even his relationship with his horse, Bucephalos, speaks volumes.

No one could tame the beast, until young Alexander noticed it wasn’t wild, just misunderstood.

The horse feared its own shadow.

So Alexander turned it toward the sun.

That same horse would go on to save his life in battle more than once.

Always seeing and heading towards the light

A bond built not through force, but through understanding.

Alexander wasn’t just a warlord.

He was a bridge. A storm that carved paths, not just graves.

And he didn’t conquer for gold or glory, he conquered for an idea.

That civilization, true civilization, isn’t about domination.

It’s about elevation.

Because at his core, he believed in the Hellenistic mind

In the idea that man is capable of reason, virtue, and greatness.

And that even the “barbarians,” once taught to read Greek, once exposed to lives of honor and greatness, would want to become great themselves.

Not by command, but by example.

Kind of like what’s happening in your own mind as you read this.

Alexander the Great and the Tragic Fate of Thessaloniki

According to legend, Alexander the Great had a stepsister on his father’s side, King Philip II (359-336 B.C.). Her name was Thessaloniki, a name that would echo not just in history but in myth, bearing both glory and tragedy.

The myth unfolds around Alexander’s relentless pursuit of the water of immortality. Though versions of the tale diverge, they converge on a moment when Thessaloniki becomes entwined with this fateful quest.

In one telling, Thessaloniki, driven by envy or ambition, drinks the water first, hoping to claim the immortality her brother sought. Her act does not go unpunished. Alexander, enraged by her betrayal, curses her, and in that curse, she is transformed into a mermaid, neither fully human nor fully divine, condemned to live forever in the depths of the sea.

Another version speaks not of envy but of tragedy. Here, Thessaloniki drinks the water unknowingly, stumbling into her fate. Overcome with grief for the immortality that was never meant for her, she is turned into a mermaid by her own sorrow, her tears blending with the waves.

A gentler version imagines her as a devoted sister who, finding the water of life, brings it to her brother. But in an unexpected twist, Alexander offers it back to her, gifting her the very eternity he sought. The gesture, whether born of love or indifference, seals her fate. Immortal now, but with a life bound to the ocean’s tides, she is transformed, left to wander the endless seas.

In every retelling, despite the differing motives and outcomes, the conclusion remains the same: Thessaloniki, now a mermaid, becomes a guardian of the sea, forever asking the same mournful question to every sailor she encounters: “Sailor, sailor, is King Alexander alive?”

The answer determines her mood and the fate of those who cross her path. If the sailor answers yes, affirming Alexander’s eternal life, Thessaloniki’s heart is lifted, and she lets the ship sail on peacefully. But if the sailor dares to say no, claiming Alexander is dead, her grief turns to wrath. The waves churn with her anger, and she drags the ship and its crew to a watery grave, unleashing a storm from her endless tears.

This myth reflects not just a tale of transformation but also a deeper symbol of the unending mourning for a hero lost to time. Thessaloniki’s fate reminds us of the costs of seeking what lies beyond the mortal coil and the boundless, often destructive, sorrow that immortality can bring.

Ο Μέγας Αλέξανδρος!

All the great conquerors who existed after Alexander the Great desired to be just like him, and, hoped to accomplish much more than he did. Even Genghis Khan knew of Alexander.

Unfortunately none were as young as Alexander was and none have achieved what he did in a mere 10 years. He spread the learning and culture of Greece to millions of square miles of territory.

Also Alexander was never defeated, which cannot be said of any other conqueror in history.

He always lead his men from the front and was injured many times, yet survived until he was 32.

An age at which many conquerors had not yet begun their achievements.

Not many know this:

General George S Patton, US Army WWII believed , FIRMLY, in Reincarnation, among other areas, of "Past-Life" incarnations, as, A Greek Hoplite (seems to be Athenian) fighting against Persians, and a Soldier-in-Service to Alexander at The Battle of Tyre....He credits "His Campaign Successes" and Stratago-like Command, to The Ancient Greats!

He graduated US Army Military Academy, as Cavalry; He saved The Lipizzaner horses, then outside of Vienna, a safe area, from being taken or killed by advancing Russian Troops;

As you would know, The Lipizzaner is The Last Breed of pedigree, Battle Horses, to survive, reminds me of Bucephalus.

Lipizzaners, while born black, and most mature into white, occasionally however, some stay black.

Interesting isn’t it!

The Sarissa

Introduced by Alexander’s father, Philip II of the Greek Kingdom of Macedon for his Greek armies, Sarissa was a 4 to 7 meters long spear which was used instead of the dory. It was made of tough cornel wood and weighed around 5 kilograms. Sarissa was considerably longer than its predecessor and this made it very effective in the Macedonian phalanx which was considered invulnerable from the front and could be only defeated if the formation was broken. Invention of Sarissa greatly helped Philip II and his son Alexander the Great in their conquests. 🇬🇷

Appreciate you riding with me this far.

Alexander’s not done—and neither am I.

I’ve got more stories, more fire, more pages from Plutarch that changed how I see the world. I’ll bring them back to you.

Not just to inform—but to ignite.

Because if these stories lit something in my soul,

maybe they’ll spark something in yours.

🔥 Subscribe to fuel the fire.

💬 More tales. More truths. More of what they don’t teach you in school.

📖 Substack: sirescanor.substack.com

📺 YouTube: @HopiumSlayer & Rumble

HopiumSlayer.com 🔥

Support fuels the fire.

And the fire is just getting started.

Thank you all!

Great information and the way it was conveyed!

Wow but that made riveting reading ! every word of it - thank you so much .